The city of Berlin in the 1930s was fertile ground for advante-garde philosophers, artists, musicians and freethinkers—but it did not remain that way for long. By the end of the decade, it had turned very dark and the city that had once personified the very essence of social freedom was transformed into the epitome of political insanity.

In those few, precious years of personal and sexual liberation—before Berlin revealed its Shadow side, the city was an extremely fertile place for artisans of all persuasions to espouse their freedom philosophy.

In this state, Berlin was a magnet for a diverse wave of individuals keen to enjoy its excesses.

One of those who was never known to miss a good party was Aleister Crowley—an occultist whose ‘Do What Thou Wilt’ philosophy was in direct harmony with the energy and vibrancy of the city’s day and night life.

Crowley’s decision to relocate from England to Berlin in Germany for a few years during the early 1930s seemed to be a natural progression of both his occult studies and enabled him to bring his artwork to a German audience.

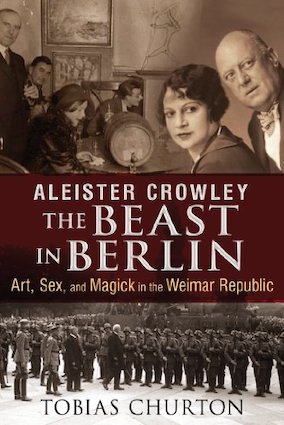

In Aleister Crowley: The Beast in Berlin, writer and researcher Tobias Churton examines this short, but important period in Crowley’s life when, at the age of 55, he introduced himself to native Berliners less as a mystic or mage and more to increase his profile as a painter.

At least, on the face of it, this was the reason for Crowley’s decision to live in the German capital. Other reasons suggest that Crowley’s real work was to act as a spy for the British secret service MI5.

According to Churton, Crowley had indicated a prior interest in relocating to Germany a couple of years earlier. In 1928, he had proposed moving to Hamburg as part of a publishing business venture with Karl Germer and Gerald Yorke.

Through his business association with Germer, Crowley evidently was keen on promoting his written works in the country and on ‘cracking the German market’ as a publishing agent might say today. The reasons for Crowley’s enthusiasm are varied but it was evident that the country had resonated with him in that pre-Nazi era to what might be described as burgeoning New Age and Thelemic spiritual ideologies.

Churton describes the basis of this rise in esoteric interest in the country at the time citing German occultist Theodor Reuss as a leading advocate of the Law of Thelema along with an increasing interest from the burgeoning Rosicrucian movement.

At this point in his life, Crowley had accepted his role as the primary ambassador for what he saw as the New Aeon. His visit to Germany gave him the opportunity to work both with the OTO and other warmly-disposed German occultists in an effort to merge all esoteric doctrines and to advance the central political and philosophical tenets of the Law of Thelema.

During his time in Berlin, Crowley also rubbed shoulders with other rising luminaries of the period. This included the popular science fiction writer J. W. N. Sullivan—who had been friends with the writer Aldous Huxley. The three of them met up and dined in Berlin following an initial introduction via Albert Einstien who also lived in Berlin at that time.

Later on, Crowley painted both Sullivan’s and Huxley’s portraits and they appeared in Crowley’s 1931 art exhibition in the city.

Despite the harmonised natures of both Crowley and Berlin, from February 1931 onward, Crowley the artist really struggled to establish himself in the city. He split his meagre resources between developing his interest in sex-magick and working to pull his first art exhibition in the city together.

Financially speaking, he was well below rock bottom at this point. He relied solely upon the benevolence of his friends to support him. His health, his business dealings and his relationships all suffered at this time.

However, Crowley staggered on and eventually, created a large enough body of artwork to justify the expense of staging an exhibition. This lasted roughly one month from September of 1931.

Whilst this was taking place, the political scene in Germany and in Berlin in particular was growing increasingly unstable. Crowley recognized that political sands were shifting…and not in his favor or to his liking. He began to express his concerns to friends and started to consider his own position as a Berliner.

His concerns about his safety in the city proved accurate. A few months later, Crowley was badly beaten up by local ruffians. He was hurt badly enough that he had to take to his bed.

This event appears to have been the final straw for, broken and penniless, Crowley finally gave up on Berlin, packed his bags and returned to England on 20th June 1932.

To wrap up the story of Crowley and Berlin, in the conclusion of Aleister Crowley: The Beast in Berlin, Churton reveals a little of the destinies that befell the main players that were so prominent in Crowley’s life during his time in Berlin.

As the author explains, the fortunes of some participants were more favorable than others. Karl Germer ended up being interred in both German and French concentration camps before being freed to escape to America where he continued to be hounded by the security services.

The book closes with a lengthy commentary on politics and consideration of a Thelemic theopolitical system based upon values of freedom and self determination and ends with a notes section and index.

Review

Tobias Churton’s book offers a colorful and detailed look at the lifestyles of those who lived in decadent 1930s Berlin. It explores the world-changing political atmosphere in the Weimar Republic at that time and details the influences and impact that the leading figures in the world of the occult and spiritualism had.

This is a deeply-engrossing story, made so much richer than it might have been through the author’s opportunity to gain access to some extraordinary material from the OTO archives. These include letters of correspondence from figures such as Karl Germer and Gerald Yorke as well as never before seen photos of The Beast himself.

The book also features a breathtaking collection of extremely rare prints, reproductions of some of Crowley’s artwork and pages from the late 1920s German occult publication Saturn Gnosis.

There are many biographies of Crowley—though few deal with this period of his life in such detail.

Do we learn anything new from this one?

We do. Whilst most Crowley biographies leave the reader with the impression that he was rather inept in matters of money (probably a fair assessment given that, during just a few short decades, he squandered the large fortune left to him by his parents’ family business), Churton paints a rather different picture of Crowley. He suggests that Crowley was actually quite an insightful businessman. The fact that he failed in most of the publishing enterprises he undertook appears to have been through factors not of his own making but due to the ineptitude of those that he worked with.

The book also reveals Crowley to be somebody with a strong scientific mind despite his evident interests in magick and metaphysics. To Crowley, the scientific and metaphysical ways of describing the universe were indistinguishable and he clearly showed great interest in the radical scientific paradigms that were emerging. Indeed, Churton refers to Crowley as a Quantum Magus

—a term that is wholly applicable to a man who coined the phrase scientific illuminism

.

Aside from the political and social commentary, the real strengths of this publication are to be found in the insights that the author provides into Crowley’s relationships with other significant acquaintances in his life. This includes fascinating information on his thoughts regarding his personal secretary Israel Regardie for whom Crowley appears to have had an abiding respect despite their age difference.

In short, this is a richly-detailed book that reveals the story behind an epoch-making period in modern history as seen and experienced both through Crowley’s eyes and those of his compatriots. In many ways, his artwork is incidental to the story which effectively reveals that, everywhere Crowley went, he left behind him a trail of effect that laid down the seeds of Thelema and a new magickal current.

Written by an author with an acute respect for detail, this is a book that draws you into the world of 1930s Berlin and the professional aspirations of Aliester Crowley in a thoroughly engaging and delightful way. No Thelemite should miss this valuable addition to the Crowley legacy.

5/5